(I will soon insert links to the recordings that are referenced here)

The music of Charles Parker Jr. – as well as the music of many other musicians – probably has the greatest influence on my own music. I view Parker as a major composer, albeit primarily a spontaneous composer. His written compositions, similar to many other very strong spontaneous composers, were mainly jumping-off points for his spontaneous discussions. Parker was also someone whose function would be analogous to the role of a master drummer in traditional West African societies. For me, Parker translated these combined ideas, via a style that is a sophisticated version of the Blues, into something that can express life, from the point of view of the African-American experience in the 20th century. Many others, John Coltrane for example, contributed to the expression of this transitional music on a technical, intellectual and spiritual level.

I get a lot of what I call micro-information from Parker. There is much in the way of technical things such as melodic movements and progressions, etc., but there are also the linguistic aspects of Parker’s music and the emotional and spiritual content. In studying the history of how this music was developed, one can glean a great deal of insight about the natural world as well as human nature in general. This story has been told many times before; the clothes may be different, but it is the same story.

In my opinion, by far the most dramatic feature of Bird’s musical language is the rhythmic aspect, in particular his phrasing and timing, not only his own playing but in combination with dynamic players such as Max Roach, Roy Haynes, Bud Powell, Fats Navarro, Dizzy Gillespie, and others. Although much more has been written about the harmonic aspects of Bird’s musical language, most of this harmonic conception was already present in the music of pianists and saxophonists from the previous era, before Parker arrived on the scene. Among others, the music of pianists Duke Ellington and Art Tatum, as well as saxophonists Coleman Hawkins and Don Byas, demonstrated an already quite sophisticated grasp of harmony. Just about any recording of Tatum demonstrates a harmonic language that rivaled anything from the musicians of Charlie Parker’s time. Furthermore, one could look at examples such as Coleman Hawkins’ famous 1939 rendition of Body and Soul or Don Byas’ 1945 Town Hall duos with Slam Stewart (I’ve Got Rhythm and Indiana) to see that many of these harmonic aspects were already quite developed. Also in Byas’ recordings, we already see some hint of the rhythmic language that would emerge fully developed in Parker’s playing.

Not a lot has been written about the rhythmic aspects of this language, and for good reason – there are no words and developed descriptive concepts for it in most Western languages. Western music theory has developed primarily in directions that are great for describing the tonal aspects of music, particularly harmony. However, the language to describe rhythm itself is not very well developed, apart from descriptions of time signatures and other notation-related devices. But over the years, musicians themselves have developed a kind of insider’s language, an informal slang that is helpful to allude to what is already intuited and culturally implied.

The implications of Parker’s phrasing helped to catalyze the rhythmic responses that eventually would come from players such as Max Roach, Bud Powell, Fats Navarro, etc. Although the descriptive aspects of these rhythmic concepts are underdeveloped, we could extend our ability to discuss this language by drawing from the perspective of the rhythmic language of the African Diaspora. Dizzy Gillespie referred to Charlie Parker’s rhythmic conception as sanctified rhythms, suggesting a style of playing that was related to music heard in church. Later in this article I will take that analogy a little further when I discuss ternary versus duple time.

There is a famous quote by Beethoven that “music is a higher revelation than philosophy.” The tradition of Armstrong, Ellington, Monk, Bird, Von Freeman, Coltrane, etc., has demonstrated to the world the great heights that spontaneous composition can be taken to, and there is great importance in this. In the West, especially sophisticated spontaneous composition became virtually a lost art, probably only kept alive in the context of the French Organ improvisational schools (Pierre Cochereau, Marcel Dupré, etc.) and some of the various forms of folk music. But the form and approach of the concept of spontaneous composition that was developed in the Armstrong-Parker-Coltrane continuum (to use a phrase coined by Anthony Braxton) and the amount of information that this form of composition projects (both material and spiritual information) is staggering in its scope. This is particularly true when you look at the relatively short amount of time that it has taken for this music to develop.

That is not to say that other forms of music have not accomplished the same thing in their own way. But this article deals specifically with spontaneous composition as expressed in the music of Charlie Parker.

I will address most of the following performances in some detail with technical analysis, and will mostly concentrate on the rhythmic, melodic and linguistic elements of Parker’s music.

1. TRACK: Ko-Ko

ARTIST: Charlie Parker

CD: Complete Royal Roost… (Savoy)

Musicians: Miles Davis (tp) Charlie Parker (as) Al Haig (p) Tommy Potter (b) Max Roach (d)

Recorded: New York, Royal Roost, September 4 1948

This is one of the slickest melodies that I’ve ever heard. And the manner in which it is played is just sophisticated slang at its highest level. The way the melody weaves back and forth is unreal, and Yard and Max keep this kind of motion going in the spontaneous part of the song.

I’m a big boxing fan, and I see a lot of similarities between boxing and music. To be more specific, I should say that I see similarities between boxing and music that are done a certain way. There was a point in round seven of the December 8, 2007, Floyd Mayweather, Jr. versus Ricky Hatton fight (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=16EGkaCHmFg), starting with an uppercut at 0:44 of this video (2:19 of the round), and also beginning with the check left hook at 2:22 of the video (0:42 of the round) when Floyd was really beginning to open up on Ricky, hitting him with punches coming from different angles in an unpredictable rhythm. If you listen to this fight with headphones on you can almost hear the musicality of the rhythm of the punches. Mayweather was throwing body shots (i.e. punches) and head shots, all coming from different angles: hooks, crosses, straight shots, uppercuts, jabs, an assortment of punches in an unpredictable rhythm. But it’s not only that Mayweather’s rhythm that was unpredictable, It was also the groove that he got into.

In my opinion, the work of Max Roach in this performance of Ko-Ko is very similar to the smooth, fluent, unpredictable groove that elite fighters like Mayweather, Jr., employ. The interplay of Max’s drumming with Bird’s improvisation sets up a very similar feel to what I saw in Mayweather’s rhythm. Near the end of Ko-Ko, at 2:15, Max does exactly this same kind of boxer motion, accompanying the second half of Miles’ interlude improvisation and continuing into Bird’s improvisation, only in this case it is like a counterpoint, a conversation in slang between Yard and Max. This is a technique that is both seen and heard throughout the African Diaspora. A certain amount of trickery is involved, a slickness that is demonstrated, for example, by the cross-over dribble and other moves of athletes: for example, the ‘ankle breaking’ moves of basketball player Allan Iverson. In addition to this, Max’s solo just before the head out is absolutely masterful. Try listening to it at half speed if you can.

This was the first Charlie Parker recording that I ever heard, as it was the first cut on side A of an album (remember those?) that my father gave me. And I can still vividly remember my response – I had absolutely NO IDEA of what was going on in terms of structure or anything else. It all seemed so esoteric and mysterious to me, as I was previously exposed to the more explicit forms of these rhythmic devices as presented in the popular African-American music that I grew up listening to. Compared to music that I had been listening to when I was younger (before the age of 17), the detailed structures in the music of Parker and his associates were moving so much more quickly, with greater subtlety and on a much more sophisticated level than I was accustomed to. However from the beginning, while listening to this music, I did intuitively get the distinct impression of communication, that the music sounded like conversations.

In discussing Ko-Ko, first of all the rhythm of the head is like something from the hood, but on Mars! In the form and movement there is so much hesitation, backpedaling, and stratification. The ever-present phrasing in groups of three and the way the melody shifts in uneven groups, dividing the 32 beats into an unpredictable pattern of 3-3-2-2-3-3-2-2-1-3-4-4. By backpedaling I mean the way that the rhythmic patterns seem to reverse in movement – for example the 8s are broken up as 3-3-2, then as 2-3-3. By hesitation I am referring to the way the next 8 is broken up as 2-2-1-3, as kind of stuttering movement.

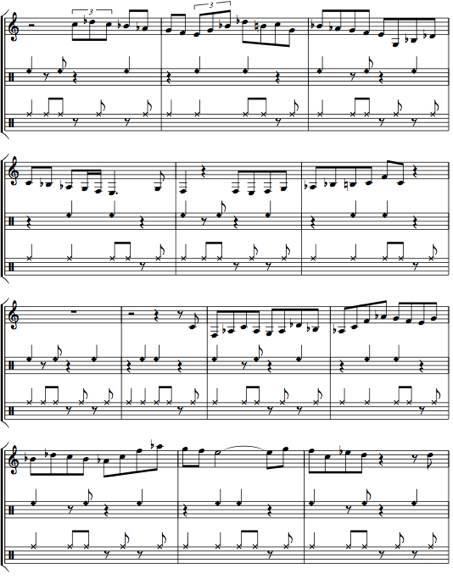

Opening melody of Ko-Ko

Stratification is just my term for the funky nature of the melody and Max’s accompaniment. With this music I have always paid more attention to the melody, drums and bass – however, this song form is composed of only melody and drums, with Max’s part being spontaneously composed. The way Max scrapes the brushes rhythmically across the snare, frequently pivoting in unpredictable places, adds to the elusiveness and sophistication of this performance. For example, during the head and under Miles’ first interlude improvisation (starting at measure 9), Max provides an esoteric commentary, filling in a little more as Parker enters (in measure 17) – however, the beat is always implicit, never directly stated. On this rendition of Ko-Ko, Bird’s temporal sense is so strong that his playing provides the clues for the uninitiated listener to find his/her balance.

Melody of Ko-Ko, trumpet, sax, snare & bass drum

One rarely hears this kind of commentary from drummers, as much of today’s music is explicitly stated. The way Max chooses only specific parts of the melody to use as points for his commentary is part of what makes the rhythm so mysterious. Much is hinted at, instead of directly stated. This continues in the spontaneously composed sections of this performance, as Yard plays in a way where there are very hard accents which form an interplay with Max’s spacious exclamations. Punches are being mixed here, some hard, some soft, upstairs and downstairs, in ways that form a hard-hitting but unpredictable groove. I’ve always felt that the obvious speed and virtuosity of this music obscures its more subtle dimensions from many listeners, almost as if only the initiates of some kind of secret order are able to understand it. This kind of slickness and dialog continues throughout this performance, building in ways that ebb and flow just as in a conversation. By the way Miles plays the F in measure 28 early – but based on the original 1945 studio recording with Diz and Bird playing the melody, this F should fall on the first beat of measure 29. However, Yard and Max play their parts correctly, so the still developing Miles Davis probably had trouble negotiating this rapid tempo.

Spontaneously composed music can be analyzed in a similar fashion to counterpoint, in terms of the interaction of the voices. However, it is a counterpoint that has its own rules based on a natural order and intuitive-logic – what esoteric scholar and philosopher Schwaller de Lubicz referred to as Intelligence of the Heart. Also, in my opinion, the cultural DNA of the creators of this music should be taken into account, just as you should take environment and culture into account when studying any human endeavors. Max tends to play in a way that both interjects commentary between Bird’s pauses and punctuates Parker’s phrases with termination figures. For a drummer to do this effectively he/she must be very familiar with the manner of speaking of the soloist in order to be able to successfully anticipate the varied expressions.

I have heard many live recordings where it is clear that Max is anticipating Parker’s sentence structures and applying the appropriate punctuation. This is not unusual – close friends frequently finish each other’s sentences in conversations. With musicians such as Parker and Roach everything is internalized on a reflex level. As this music is rapidly moving sound being created somewhat spontaneously, I believe that the foreground mental activity occurs primarily on the semantic level in the mind, while the internalized, agreed upon syntactic musical formations may be dealt with by some other more automated process, such as theorized by the concept of the mirror neuron system. What is striking here is the level that the conversations are occurring on – these are very deep subjects! Most of the time, critics and academics discuss this music in terms of individual musical accomplishments, and don’t focus enough attention on the interplay. I feel this music first and foremost tells a story. There is definitely a conscious attempt to express the music using a conversational logic. So what I am saying is that while syntax is important, semantics is primary. Too often what the music refers to, or may refer to is ignored.

The last half of the bridge going into the last eight before Roach’s solo (at 1:32) provides one of these rhythmic voice leading points where Max goes into his boxing thing, playing some of the funkiest stuff I’ve heard. Just as instructive are the vocal exclamations of the musicians and possibly some initiated members of the audience, which form additional commentary. There is so much going on in this section that you could write a book about it – an entire world of possibilities is implied, as the rhythmic relationships are far more subtle than what is happening harmonically.

2nd half of last bridge and last 8 of Ko-Ko, Bird’s solo

This illustrates that on these faster pieces Yard tended to play with bursts of sentences punctuated with shorter internal groupings using hard accents, whereas Max played in a way that effectively demarcated Parker’s phrases with longer groupings setting up shifting epitritic patterns*. Max sets these patterns up by repeated figures designed to impress upon the listener a particular rhythmic form, only to suddenly displace the rhythm from what the listener was conditioned to expect. The passage above is a perfect example of this, setting up a hypnotic dance of 2-3-3, only to shift the expected equilibrium with the response of 2-1-3-1-1, then continuing with a slight variation of the initial dance.

Even the vocal exclamations of the musicians and audience members participates in what I consider to be secular ritualized performances. All of these features that I mention are traits that I consider to be a kind of musical DNA that has been retained from Africa. This music’s level of sophistication demanded the intellectual as well as emotional participation of musicians and non-musicians alike (when they could get into the music, which not all people could). The rate of change of each instrument is also instructive. Obviously the soloists are in the foreground playing the instruments that have the swifter motion. In the case of this particular group, the bass would be approximately half the speed of the soloist, with the drums having a mercurial and protean function. In terms of commentaries, the drummer would be the next slowest after the bass and piano, and would be providing the slowest commentary from a rhythmic point of view. However, elements of the drum part are closer to the speed of the soloist.

*The epitritic ratio is 4 against 3 – that is, Max playing the 4 against slow 3 (i.e. a slow pulse which is every 3 measures of 1/1 time). This ratio is used a lot on the continent of Africa.

2. TRACK: Celebrity

ARTIST: Charlie Parker

CD: Charlie Parker – The Verve Years 1950-1951 [Verve VE2 2512]

Musicians: Charlie Parker, alto saxophone; Hank Jones, piano: Ray Brown, bass; Buddy Rich, drums

Recorded: New York, October 1950

Unlike Ko-Ko, I included this cut because of the lack of dialog between Parker and Buddy Rich (drums), who plays more of a time-keeping role here. As a result Bird’s phrases stand out more against the relief of a less involved backdrop. Here we can concentrate on the question and answer qualities of Parker’s playing as well as on the melodic and harmonic content. The harmonic structure of the song is based on one of the standard forms of this time period, Rhythm Changes, derived from the George and Ira Gershwin composition I Got Rhythm.

In my opinion, the main keys to Bird’s concept are the movement of the rhythm and melody, with the harmonic concept being fairly simple. Not only has this been communicated to me directly by several major spontaneous composers of that era, but one can find quotes from musicians of this period stating this idea, such as the following from bassist and composer Charles Mingus:

“I, myself, came to enjoy the players who didn’t only just swing but who invented new rhythmic patterns, along with new melodic concepts. And those people are: Art Tatum, Bud Powell, Max Roach, Sonny Rollins, Lester Young, Dizzy Gillespie and Charles Parker, who is the greatest genius of all to me because he changed the whole era around“. (Liner notes to Let My Children Hear Music)

If you have not read these liner notes by Mingus you should really check them out: http://www.mingusmingusmingus.com/Mingus/what_is_a_jazz_composer.html

It is clear that from Mingus’ perspective, it is the rhythmic and melodic concepts that are the real innovations of this music. On the one hand, Mingus refers to rhythmic and melodic innovation and sophistication, things that could keep a musician interested from the perspective of the craft of music. At other points in the article Mingus talks about the necessity that the spontaneous compositions be about something, that they tell a story about the lives, experiences and interests of the people performing the songs or of other people, and that these are principles that transcend the craft of music as a thing and move toward the core of what it is to be human. I see Bird’s music as fitting squarely within this tradition, whatever name it may be called by.

I’ve always thought of Bird’s spontaneous compositions as explanations containing various types of sentence structures. Here, after Buddy Rich’s drum introduction, Parker begins Celebrity with a 27-beat opening statement, but within this statement is an internal dialog. The harmony and timing help to structure the statement, and gives the listener a sense of the dialog. Generally speaking, what I call dynamic melodic tonalities suggest open ended sentences which are usually (but not always) followed by a response, and in fact lead to or invite a response.

Opening (8 beats – static to dynamic)

Response (8 beats – preparation to dynamic)

Elaboration (8 beats – dynamic to static)

Closing (2 beats)

New Opening (8 beats – static to dynamic)

Response (8 beats – preparation to dynamic)

Extension (7.5 beats – dynamic to dynamic)

Semi-Closing (6.5 beats)

First 16 measures of melody of Celebrity

Following up on what Mingus referred to as “new melodic concepts”, many times musicians use what I call Invisible Paths, meaning that they are not necessarily following the exact path of the composed or accepted harmonic structure for a particular composition, but instead following their own melodic and harmonic roads which functionally perform the same job. The musical description of that job is to form dynamic roads that lead to the same tonal and rhythmic destinations as the composed harmony. This differs slightly from the academic concept of chord substitutions, because these Invisible Paths can be entire alternate roads that are not necessarily related to the composed harmony on a point-by-point basis, and resist being explained as such, but nevertheless perform the same function of voice leading to the cadential points within the music. These paths may be rhythmic, melodic or harmonic in nature – all that is required are the same three elements that are required with a physical path – an origin, a path structure and a destination.

Many older musicians, especially the self-taught musicians with less training in European harmonic theory, have told me that the musicians of that time were primarily thinking in terms of very simple harmonic structures, mostly the four basic triads (major, minor, diminished, augmented) along with some form of dominant seventh chords. Although the harmonic structures were simple, the different ways in which they progressed and were combined were complex, again pointing to the idea that it was the movement of the musical sounds that most concerned these musicians. This is often overlooked by academics who are used to analyzing music by relying on the tool of notation, instead of realizing that music is first and foremost sound, and sound is always in motion. It was in the areas of rhythm and melody where most of the complexity was concentrated. Many of these musicians did not learn music from the standpoint of music notation, so they had a more dynamic concept of the music closely allied with how it sounded rather than how it looked on paper. Unfortunately, for copyright reasons, this website cannot allow me to use sound examples for this article, so, ironically, I will myself be forced to use notation. My choice would be to use geometric symbols and diagrams. However, I would then need to spend a large sections of this article explaining the symbols.

In analyzing these passages, we can sometimes see hybrid structures or harmonic schemes which shift in the course of a single melodic sentence. Coming out of Buddy Rich’s solo, a simple version of this idea seems to be along the following path, or something similar, for 32 beats.

1st 8 (after drum solo) of Bird’s solo on Celebrity

|| Cmin7 F7 | Bb A7 | F7 Dbmin6 | Cmin7 F7 | Fmin7 Bb7 | Ebmaj Ebmin | Bbmaj | C7 F7 ||

The bridge is even more varied, with Bird’s melodic paths creating their own internal logic, which then resolve back into the logic of the composition.

Last bridge of Bird’s solo on Celebrity

|| Ebmin6 | Amin6 Ebmin6 | Dmin | Fmin6 | Gmin6 (maj7) | Gmin6 | Cmin6 | (F7) ||

With a little thought, you will notice that these passing tonalities provide the same function as the composed harmonic structure of the song. Notice here that Yard is doing just what he stated in two different versions of the same quotation:

“I realized by using the high notes of the chords as a melodic line, and by the right harmonic progression, I could play what I heard inside me. That’s when I was born.” ( c. 1939 quoted inMasters of Jazz)

“I found that by using the higher intervals of a chord as a melody line and backing them with appropriately related changes I could play the thing I’d been hearing. I came alive.” (1955 Hear Me Talkin’ to Ya)

However, Parker’s version of “higher intervals of a chord” was not in the form of flatted 9ths, 11ths and 13ths, but in the form of simple melodic and triadic structures that reside at a higher location within the tonal gamut which I refer to as the Matrix (who really knows how Bird thought of it?). In this case, simple minor structures such as Ebmin6, Amin6 and Fmin6 are the upper intervals of Ab7, D7 and Bb7, respectively. These minor triads with an added major sixth are very important structures in music, often mistakenly called half-diminished (for example Amin6 could be called F# half-diminished today). In this instance, the function of Amin6 is that of dynamic A minor, in the same sense that the function of D7 is that of dynamic D major. By dynamic I mean energized with the potential for change. Adding a major 6th to a minor triad has a similar (but reciprocal) function to adding a minor 7th to a major triad, and that function in many cases is to energize the triad, to infuse it with a greater potential for change, due to the perceived unstable nature of the tritone interval. Pianist Thelonious Monk was a master of this technique, and demonstrated this to many of the other musicians of this time (including Dizzy and Bird). Regarding whether to use the name half-diminished or minor triad with the added 6th, this is a case where a simple change in name can obscure the melodic and harmonic function of a particular sound. Dizzy Gillespie mentions this in his autobiography when he says that for him and his colleagues, there was no such thing as half-diminished chords – what is called a half-diminished chord today, they called a minor triad with a major sixth in the bass.

“Monk doesn’t actually know what I showed him. But I do know some of the things he showed me. Like, the minor-sixth chord with a sixth in the bass. I first heard Monk play that. It’s demonstrated in some of my music like the melody of “Woody ‘n You,” the introduction to “Round Midnight,” and a part of the bridge to “Mantaca.”…. There were lots of places where I used that progression… and the first time I heard that, Monk showed it to me, and he called it a minor-sixth chord with a sixth in the bass. Nowadays, they don’t call it that. They call the sixth in the bass, the tonic, and the chord a C-minor seventh, flat five. What Monk called an E-Flat-minor sixth chord with a sixth in the bass, the guys nowadays call a C-minor seventh flat five… So they’re exactly the same thing. An E-Flat-minor chord with a sixth in the bass is C, E-flat, G-flat, and B-flat. C-minor seventh flat five is the same thing, C, E-flat, G-flat, and B-flat. Some people call it a half diminished, sometimes.” (from the chapter Minton’s Playhouse in to BE, or not… to BOP)

3. TRACK: Perhaps – Take 1

Artist: Charlie Parker

CD: The Complete Savoy Studio Sessions [Savoy SJL 5500]

Musicians: Miles Davis (tp) Charlie Parker (as) John Lewis (p) Curly Russell (b) Max Roach (d)

Recorded: New York, September 24 1948

This composition is another example of the many linguistic rhythmic devices Parker used in his music that are not much discussed. In my opinion, the composed melody is clearly an explanation with variations. The opening phrase of the melody is an explanation of some kind, followed by “but perhaps” (going into measure 5), which begins the first alternate explanation. Then “perhaps” (into measure 7) begins a second alternate explanation. “Perhaps” (into measure 9) begins the final clarification, then the melody ends with the responses in measures 11 and 12 – “perhaps, perhaps, perhaps.” Therefore we can think of the melodic segments in between the “perhaps” as some sort of discussion and clarification of a particular situation, lending more evidence to the literal admonishment of the cats to “always tell a story” with your music. Obviously in this song there is an added onomatopoetic dimension to the melody that allowed me to at least recognize the perhaps musical phrase at an early stage in my career when I knew very little about the structure of music. But this more obvious example also served notice to me that these possibilities existed within this music, and just maybe there also were elements of the spontaneous compositions that exhibited these features.

This was my intuitive reaction to this song when I first heard it in my formative years as I was still learning how to play, and it is still how I understand it when I listen today. But beyond the more obvious example of this composed melody, I feel that the spontaneous part of this composition, indeed of all of Parker’s compositions, are also explanations, and that they are all telling stories. And as mentioned before, they contain the same kinds of exclamations, dialog, linguistic phraseology, and common sense structure that is contained in everyday conversation, with the exception that this linguistic structure is based on the sub-culture of the African-American community of that time, what most people would call slang. This is particularly evident in the rhythm of the musical phrases. The way Max answers the melody is definitely conversational. I hear the same kinds of rhythms that I see when watching certain boxers, basketball players, dancers, and the timing of most of the various activities that go on in the hood. However, this same rhythmic sensibility can occur on various levels of sophistication, and with the music of Bird and his cohorts, it occurs on an extremely sophisticated artistic level.

This subject of musical conversation brings up the issue of African-Diapora DNA. Scholar Schwaller de Lubicz made reference to a theory that the ancient Egyptians, at some very early point in their existence, had a language whose structure and utterances consisted of pure modulated tones similar to music, as opposed to the phonetic languages of today. Given that their ancient writing contained no symbols for vowels, this idea may seem far-fetched. However, because the recorded writing of this civilization documents over two millennia, a great deal of change must have occurred within the language.

Many modern linguists believe somewhat the opposite, that the original human languages contained clicks or were predominantly click languages. These linguists use the languages of the Hadza people of Tanzania and Jul’hoan people of Botswana as evidence. However, the evidence of drum languages in the Niger-Congo region of Sub-Saharan Africa tells another story. For example, the drum languages of the Yoruba of Nigeria, Ghana, Togo and Benin; the Ewe of Ghana, Togo and Benin; the Akan of Ghana; and the Dagomba of northern Ghana, still exist today. In the languages of these areas, register tone languages are common, where pitch is used to distinguish words (as opposed to contour, as in Chinese). Since many of these West-African languages are tonal, suprasegmental communication is possible through purely prosodic means (i.e. rhythm, stress and intonation). There is little doubt that emotional prosody (sounds that represent pleasure, surprise, anger, happiness, sadness, etc.) predated the modern concept of languages. If the early ancient Egyptians developed a highly structured form of suprasegmental communication, it is quite possible that de Lubicz’ theory is correct. In any case, there is plenty of precedent for the exclusive use of tones as language.

Regarding the sections containing spontaneous composition, of course, many musical devices are involved, rhythmic, melodic, harmonic and formal, all on a very high level. Which is why most students of this music are absorbed in the musical parameters – there is so much there. But I propose that much of what is being accomplished musically can be seen more clearly if we take into account the perspective of the African-Diaspora, rather than have discussions primarily about harmonic structure, etc. Many of the rhythms that Parker uses are not merely related to African music in the linguistic sense that I have outlined above, nor only related to the notion of having a certain kind of swing or groove. Also many of the structural rhythmic tendencies of the Diaspora have been retained within African-American culture.

We can start by looking at the concept of clave in Parker’s playing. The phrase at 0:26 of take 1 is precisely the kind of slick musical sentence that Parker was renowned for among his peers. I feel that the emphasis in the phrasing contains rhythmic figures very similar to various clave patterns. This phrase is repeated almost verbatim at 0:55 with the addition of a turn and a slight shift in the clave pattern:

![]()

(at 0:26 )

![]()

versus:

![]()

(at 0:55)

Of course, you need to listen to the recording to get a feel for the emphasis, but my point here is that there does not seem to be much discussion of this aspect of Bird’s internal sense of rhythmic structure. Recognition of a sense of clave in Parker’s playing is a key (pardon my pun) to beginning to investigate his complex rhythmic concepts in greater detail. It would be instructive to listen to Bird’s spontaneous compositions only for their rhythmic content without regard for the pitches. Then it would be revealed that many of his phrases contain the same kinds of rhythmic structures found in the phrasing of the master drummers of West Africa, with the exception of the pitch conception. An investigation of the starting and ending points of Parker’s phrases reveals a kinship to these Sub-Saharan drum masters.

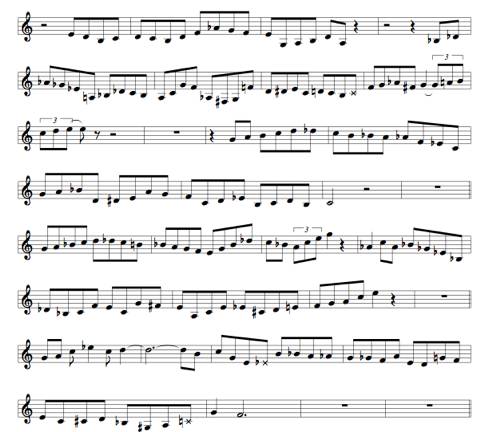

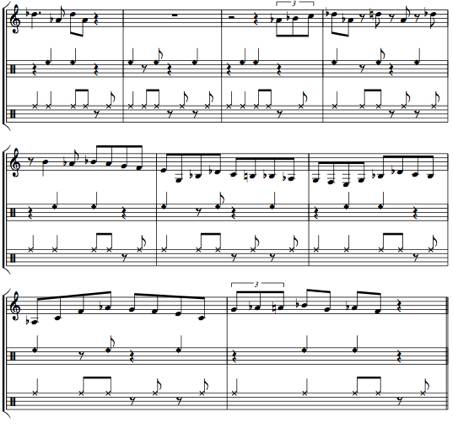

Take as an example this melodic sentence at 0:38 of take 1 of Perhaps:

There are several rhythmic shifts of emphasis here that suggest a compressing and lengthening of phrases. Starting on beat 3 of measure 2, the shift in emphasis within the phrase suggests groupings of 6-4-5-3-4 (in 4th note pulses). This concept is similar to the classic mop-mop figure, i.e., 4-3-5-4, and is one of the hallmarks of Bird’s spontaneous compositions.

4. TRACK: 52nd Street Theme #275, #238, #218, #214

ARTIST: Charlie Parker

CD: The Complete Benedetti Recordings of Charlie Parker, Three Deuces and Onyx Club (Mosaic)

Musicians: Miles Davis (tp) Charlie Parker (as) Duke Jordan or Al Haig (p) Tommy Potter (b) Max Roach (d)

Recorded: New York, July 1948

These various performances of Parker, recorded by saxophonist Dean Benedetti, demonstrate the combination of looseness and tightness of this particular band, which I consider Bird’s most effective working band. I heard about these recordings before I knew they physically existed, and I even heard a few of them long before this box set came out, so it was a real pleasure to finally hear the entire collection. For economic reasons, Benedetti usually only recorded the solos of Parker and not the other musicians, so these recordings are quite fragmented. Furthermore the sound quality is frequently poor – these are not recordings that audiophiles will be writing home about. However, for musicians studying this music, this collection is a goldmine. I compare it to finding a new ancient tomb in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, in terms of the musical treasures it yields.

4(a). TRACK: 52nd Street Theme #275

This version of Monk’s composition was usually played as a break tune, a signal that the set is coming to a close. This take is really just a fragment (similar to a find in an archeological dig), but man, it swings hard! When Parker’s sax solo enters after he speaks to the audience, the band settles into a serious groove, everybody responds to Yard, and the beat lays back to the extreme, giving the impression that the band is slowing down.

Bird’s solo on 52nd Street Theme #275

It’s clear that this groove emotionally hits those who are present, as can be heard by the various exclamations. This reaction from the people is what I love about live recordings in general – at least recordings done in the presence of responsive audiences. The steady rhythm of the rising spontaneous melody that Yard plays in the opening eight measures creates tension and is perfectly offset by the snaking melody of the second eight, with its dancing, shifting, clave-like patterns that begin in the 11th measure (at 0:42):

Rhythm of the clave-like pattern at measure 11 of 52nd Street Theme #275:

![]()

Again, this demonstrates the use of rhythms that reveal elements retained from West-African concepts.

4b. TRACK: 52nd Street Theme #238

This version is also very dynamic. I love the space that Bird utilizes in this very loose version. Right from the beginning, when Parker plays the augmentation of the melody, we know that he is on top of his game. He does not even bother to complete the melody, immediately launching into a spontaneous statement. The bridge is beautiful! Obviously Parker meant to play the melody here, but stumbles a little. But he sounds like Michael Jordan here, if you follow what I mean, by adjusting in midstream and turning his misstep into a beautiful melodic statement where antecedent and consequent are both preceded by the same rhythmic misstep (mm 1 and 5 below), which transform the original stutter into part of the form of the statement. As with many of Bird’s conversations, the form of the statement is irregular but makes perfect rhythmic sense in terms of balance, one of the traits that distinguishes him from most of his musical colleagues. Also the many alternate tonal paths and delayed resolutions (6th, 7th and 9th measures of bridge) add to the hipness of the statement.

Bridge: 2-beat stutter – 6-beat antecedent, 3-beat stutter – 18-beat consequent of 52nd Street Theme #238

Starting from the second eight of the first chorus of the solo we hear the kind of smooth melodic voice leading that Parker popularized in this music.

2nd eight, Bridge and last eight of 52nd Street Theme #238

These types of clear and precise statements were already present in the music of some spontaneous composers, such as tenor saxophonist Don Byas. However, it was through Parker’s dynamic performances that most musicians were exposed to this concept, due in large part to Bird’s unique phrasing and advanced rhythmic conception. Both Byas and Yard were from the Midwest and both had that Midwest sanctified rhythm thing happening. Byas was from Muskogee, Oklahoma, and Bird developed his musical skills in Kansas City, Missouri, although he was born in Kansas City, Kansas. The Midwest produced many great musicians. For example, Oscar Pettiford, was a fantastic bass player from Okmulgee, Oklahoma, who made tremendous contributions to this music, although these contributions are rarely acknowledged in proportion to their importance. Both Muskogee and Okmulgee are in the eastern part of Oklahoma, just south of the Kansas City metropolitan area, so this area of the country was a hotbed of activity during the 20s, 30s and 40s.

The slickness of the rhythmic concept in this example is striking. There are several clave-like rhythms where Parker plays in groups of 3 pitches, which tends to produce shifting rhythmic patterns. Overall Bird had a very rhythmic conception, even in his formative years, and it was this conception that most contributed to the change in the direction of the music during that time. Consider this statement by Dizzy Gillespie:

“I guess Charlie Parker and I had a meeting of the minds, because both of us inspired each other. There were so many things that Charlie Parker did well, it’s hard to say exactly how he influenced me. I know he had nothing to do with my playing the trumpet, and I think I was a little more advanced, harmonically, than he was. But rhythmically he was quite advanced, with setting up the phrase and how you got from one note to the other. How you get from one note to the other really makes the difference. Charlie Parker heard rhythm and rhythmic patterns differently, and after we had started playing, together, I began to play, rhythmically, more like him. In that sense he influenced me, and all of us, because what makes the style is not what you play but how you play it.” (Giant Steps: Bebop and The Creators of Modern Jazz 1945-65)

I would like to emphasize here that Charlie Parker’s rhythmic contribution amounts to more than just phrasing. Usually people write about triplets, so-called pick-up notes, etc. These perspectives reveal more about the musicologist’s academic background than they do about Parker’s sensibilities. Rhythm was something that was constantly stressed in the African-American communities – as Dizzy mentions, it was associated with the way and the how something was done. In my opinion, not only was Bird’s phrasing important, but also his placement of entire musical sentences and how they balanced each other.

4c. TRACK: 52nd Street Theme #218

What I like about this version of 52nd Street Theme is the form of the first chorus, which sets up the rest of the performance, and this partly illustrates what Dizzy was referring to in his quote. This is a true example of spontaneous composition and how the micro-forms can be very complex. One cannot underestimate the power of developed intuition and insight, when coupled with preparation, logic and talent – and Yard’s performance is a clear example of this.

At first listening, the phrases may seem to sound very symmetrical and smooth, yet a cursory observation reveals what at first appear to be random starting and stopping points with no clear balancing points. A more detailed examination exposes a sophisticated natural symmetry. The first antecedent is approximately 3 measures long, answered by what feels like a 5-measure consequent. This division of an approximately 8-measure space into 3 and 5 measures is something that has been discussed throughout history as being related to the proportion of the Golden Mean. Much has been written about this kind of balance on the Internet and in books, so I will not go over it in detail here. However, the linguistic quality is the result of rhythm and melody, and the timing of the phrases and their contour contribute to the effectiveness of the music.

The opening phrase is cryptic in the sense that it creates a lot of motion within a compact contour. There is a lot of doubling back (what we used to call going back for more) that is reminiscent of one of former NBA basketball player’s Tim Hardaway’s killer crossover moves, and Yard is truly breaking ankles here. The answer in measure 3 contains its own paraphrase, with the phrase in Gbmaj being woven into its answer in Fmaj (a 5-5-4 balance in terms of 8th note pulses) before mutating into another ankle breaking phrase from which Parker eventually achieves escape velocity. The next phrase feels perfectly centered within the second 8 measures, being contained in the internal 4 measures of the 8, however in reality it is shifted forward in time by one beat.

The ‘question and answer’ in the bridge has that same kind of Golden Mean balance, i.e., a 3-5 measure grouping to the phrases. After one of those preacher-like exclamations to begin the last 8, the final phrase has a beautiful and subtle voice leading device where Bird plays a ghosted Eb (3rd measure after the bridge) which announces a more complex sentence. This phrase also seems to wake Max up, as he becomes much more responsive at this point.

Here Parker’s melodic choices are brilliant, seamlessly alternating between diatonicism, voice leading chromaticism that is very carefully placed, and pentatony. As for the phrasing, Bird’s sentences have the quality of someone speaking with a southern accent. If you listen carefully, there is a slight drawl to the phrases, a slightly behind-the-beat drag similar to the way people talk in the south, or in the hood.

1st chorus of 52nd Street Theme #218

4d. TRACK: 52nd Street Theme #214

This version begins in progress, near the end of the 5th measure, but who knows how long Bird had already been playing. I paid a lot of attention to this version of 52nd Street Theme, as it is very intricate with a lot of great interaction. However, I will only briefly comment on each section.

The first chorus has Parker’s typical conversation-like phrases. One thing that stands out is the repeated five-note figure that occurs beginning on the 4th beat of the 4th measure of the bridge (0:13 into the performance). What is intriguing is the rhythm, where there is diminution in the amount of time between the phrases. The first phrase begins on the 4th beat of the 4th measure and ends on the 2nd beat of the 5th measure. This is repeated 2 beats later, beginning on the 4th beat of the 5th measure and ending on the 2nd beat of the 6th. Then, as the phase shifts in tonality from the secondary dominant to the dominant, Bird immediately begins the phrase again, this time starting on the 3rd beat of the 6th measure and ending on the 1st beat of the 7th measure. Passages like this always made me feel that Parker was keenly aware of not only melodic target points, but rhythmic target points also, always balancing the starting and ending points so that the phrases, even when seemingly starting in strange places, always fall exactly in balanced proportions. In other words, Bird was very attentive to melodic and rhythmic forms, but as Dizzy mentioned, the real deal is the placement of the phrases.

The second chorus begins with an aborted attempt by in Parker to play a typical lick of his that comes from clarinetist Alphonse Picou’s variation on the 1901 Porter Steele march High Society, a phrase that Bird frequently quoted (for example at the start of the second chorus to his famous 1945 Ko-Ko performance). It is clear that when playing this phrase Parker’s G# key sticks on his saxophone – the bane of all saxophone players. However, Parker quickly un-sticks the key, changes directions in midstream, and continues with a flawless execution of his improvisational statement. Two clues help me draw this conclusion. First, he succeeds in playing G# nine beats later in an immediately succeeding phrase (keep in mind this tempo is blazing). Second, while watching the video of the 1952 broadcast of Bird and Diz playing Hot House, I noticed that Bird had an ability to very rapidly fix problems with his horn, when just before the bridge during the melody he un-sticks his octave key, again in mid-flight. When I was first learning this music, I saw many other musicians do this kind of thing, notably the great Chicago tenor saxophonist Von Freeman.

The start of the second 8 also begins with an aborted quote. I’m not sure of the source of the quote (it sounds to me like it’s from an etude book), but I have heard Parker play it many times, for example, in performing his blues called Chi Chi and in other songs – so I know it should move something like this:

![]()

![]()

However Yard stumbles a bit and it comes out like this, including the spontaneous recovery, again a demonstration of how fast his mind worked:

![]()

Max’s response to the phrase in the last eight is again one of those funky dialogs. Max sets up this hip transition with the single snare hit right after Parker’s repeated blues exclamation, then two snare drum hits in between Yard’s phrases, followed by one of those funky ratios, this time 4 against 6, that is Max’s bass drum playing the 4 against the cut-time 6 of the beat, again timed to end on the measure before the top. I tend to think of this kind of playing as targeting, a technique where you calculate (using either feel, logic or both) the destination point in time where you want to resolve your rhythm, a kind of rhythmic voice leading. I alluded to Bird doing something similar above. I also dig the spontaneous counterpoint commentary of one of the listeners during this phrase, which seems to go with what Yard and Max are doing.

The next four choruses keep up the heat, and there is a lot to learn from the various techniques. Some highlights are Bird playing in layers of phrases in 3-beat groupings (0:53), the contrasts of light-to-dark-to-light beginning with the secondary dominant in the bridge at 1:04, the extreme cramming in the bridge at 1:26, the modulating descending octatonic figures (i.e. diminished) at 1:44 (which function as cycles of dominant progressions), the diminution effect in the consequent phrase at 2:12 (somebody in the audience dug it also), the extremely melodic phrase at 2:15, and finally the funky way that Max sets up the fours between Bird and Miles – which Max continues leading into and throughout the fours. The way Max Roach shifts to the hi-hat moving into the fours, and intensifies his interactions with the horn players, also demonstrates his compositional approach to playing spontaneously.

The fours are off the hook, brilliant, beginning with Parker’s ultra-melodic opening. The phrase he plays at 2:46 is unusual even by Bird’s standards, as it begins in a very dark dominant tonality, progresses to a bright, dominant sound, then anticipates the move to the subdominant with the last tritone. The energy that this phrase generates is resumed at 2:52 (after Miles’ statement) with a pair of brilliantly placed ascending tritone progressions, unusual in their rhythm and tonal progression. The rhythm is similar to the 4-against-3 patterns that Max has been executing, where the basic pulse of the song is seen though a different perspective (that of 3 against Bird’s 4). And although the tonal implications are too difficult to fully explain here, these 8 tones – Bb-E-Bb-E progressing to B-F-B-F – functionally serve to reverse the normal tonal gravity by approaching the dominant tonality (the G7 matrix) from a 5th below instead of from the normal 5th above. There exists an entire theory based on polarity that can explain this kind of movement (see the section ‘A Theory of Harmony‘ elsewhere on this website), but here it is enough to say that the naked expression of these tritones permits an ambiguous interpretation. The Bb-E-Bb-E tritone could be seen to be the functional equivalent of the tonal spectrum represented in part by C7, F#7, Gmin6, Dbmin6 (any or all of these dominant chords, and yes, I consider a minor 6th chord as potentially having a dominant function). Likewise the B-F-B-F tritone could be functionally seen as G7, C#7, Dmin6, Abmin6 – therefore, the progression represents the fairly dark transition of tonalities in progressions of ascending 5ths, which I associate with lunar energies.

This tritone phrase is a continuation of the tritone ending of Bird’s previous phrase. To my ears, Miles does not seem prepared to respond to this statement. Bird is playing in a rapid stream of consciousness manner, where each idea picks up from the last, interspersed with Miles’ responses. At 2:59, Yard continues this dark-to-light sound, giving us the third consecutive statement where he appears to be tonally emerging from a dungeon, and it becomes clear that he is on a roll. Even his entrance into the bridge is a continuation of this approach, as he approaches from the dark side, 7 flats or the mode of Gb Mixolydian, and, after a snaking Gdim turn, emerges into the sunlight of F major. This gives us his 4th consecutive lunar progression. Parker ends with a phrase that is a functional reprise of the descending octatonic figures earlier in the performance – however this sentence ends with a rocking melodic progression functioning as dominant – subdominant – dominant. Obviously he was at his creative peak this night.

5. TRACK: Ornithology

ARTIST: Charlie Parker

CD: One Night In Birdland [Columbia JG 34808]

Musicians: Fats Navarro (tp) Charlie Parker (as) Bud Powell (p) Curly Russell (b) Art Blakey (d)

Recorded: radio broadcast, Birdland, NYC, May 15 & 16 1950)

I have owned several versions of this exact recording, and almost all of them are technically flawed in one way or another. My most complete version is a CD re-mastered with the help of master drummer Kenny Washington, who pitch-corrected the recording. Also the complete Bud Powell solo is present in this recording, whereas on my original LP edition that I still own, Bud’s solo was edited out.

These performances are some of the strongest that I have heard from these participants, but what makes this recording great for me is the fact that they are all performing and interacting together. Blakey provides a totally different kind of drum accompaniment than Max Roach. Nevertheless, Art’s driving rhythms are very effective. But it is the front line of Parker, Navarro and Powell that is simply off the hook! Each soloist’s performance is beyond words. These cats are truly spontaneous composers at the top of their game, their statements so precise they could have been composed on paper.

The first thing we hear is Bud’s meandering intro, very loose as always, which starts harmonically as far away from his D pedal as possible, sliding from Ab major to A minor to Gmaj into Bird’s opening statement of the melody. Despite the impression of rubato, Bud is actually playing in time in the intro to the song. It sounds to me like Bud was already playing when the recording was started, as the first sounds we hear are measure 3, beat 3 of an 8-measure intro. At any rate, what we hear from Bud is 51/2 measures (22 beats) before Yard enters.

A book could be written discussing just this one performance, but I’ll only point out a few things here. We can learn a lot from the various versions of the spontaneous harmonies that Fats plays at the end of the melody, with the harmonization at the end of the song being different from the one at the beginning.

Fats Navarro’s harmony on top staff, at the end of Ornithology.

It seems to me that Fats’ rhythmic conception and feel was the closest to Bird’s among the trumpet players of this era. They are rhythmically as one going into the break of Bird’s soaring solo. One of my favorite sections of this recording is the woman hollering “Go Baby” right after Parker’s break, I even used to call this recording ‘Go Baby!‘

Fats Navarro’s harmony on the top staff, going into Parker’s solo on Ornithology

Parker’s melody right after this exhortation seems to rhythmically answer the woman’s voice. Bird seemed to have an intuitive grasp for the connection between musical and non-musical expressions. Parker once mentioned the connection between music and the utterances of various animals to his band mates in the Jay McShann band on a tour through the Ozarks. His music was full of oblique coded references that could be understood by his colleagues on the bandstand and those musicians in the audience who were privy to this way of communicating. Bird also directly expressed to his last wife, Chan Parker, a desire to use music in a more overtly linguistic fashion, and he mentioned this to many musicians, such as bassist Charles Mingus (Charlie Parker, by Carl Woideck, pp 214-216).

I have an audio interview that Paul Desmond conducted with Charlie Parker, where Bird mentions how telling a story with music was for him the whole point:

CP: There’s definitely stories and stories and stories that can be told in the musical idiom, you know. You wouldn’t say idiom but it’s so hard to describe music other than the basic way to describe it-music is basically melody, harmony, and rhythm. But, I mean, people can do much more with music than that. It can be very descriptive in all kinds of ways, you know, all walks of life. Don’t you agree, Paul?

PD: Yeah, and you always do have a story to tell. It’s one of the most impressive things about everything I’ve ever heard of yours.

CP: That’s more or less the object. That’s what I thought it should be.

Most people take this in a non-literal sense, but I believe that Parker and many other musicians were dead serious when they spoke of telling stories through their music, as demonstrated in the discussion of the composition Perhaps.

In the first chorus of Ornithology its immediately clear that Bird is a master at shifting the balance of his musical sentences. One example of this is how he sets up a shift in momentum by building expectation with the regularity of the phrases at 0:42 for 4 measures – which is answered at 0:46, where Bird truncates the paraphrase to 2 measures to set up the shifting clave-like phrase at 0:49 (the middle of measure 16 in my example above). This is similar to the technique that Max utilized in the Ko-Ko example that I discussed previously. This concept is difficult to explain without showing it in musical form.

I hear the phrase at 0:42 in two distinct subsections, antecedent and consequent, in terms of their melodic curves and emphases:

0:42 subsection 1a (set-up antecedent):

![]()

0:44, subsection 2a ( set-up antecedent consequent):

![]()

0:46, subsection 1b (truncated antecedent):

![]()

0:48, subsection 2b (extended shifting consequent)

clave pattern in above phrase, from the middle of second measure of subsection 2b (0:49):

![]()

The antecedent phrase at 0:42, subsection 1a, runs continuously into its consequent at subsection 2a. However, the antecedent phrase at 0:46, subsection 1b, is interrupted, followed by the extended consequent at subsection 2b (0:48), in which the rhythmic displacement or shift of emphasis occurs at around 0:49, from the middle of the 3rd measure of subsection 2b. The phrases at 0:42 (subsection 1a) and 0:46 (subsection 1b) are symmetrical in length. The following phrase, which Parker did not play, is what I imagine the consequent at 0:48 (subsection 2b) could be without the clave-like extension.

![]()

But there is even more at work here, and what I suspect is the intuitive reason that the last consequent was extended. The opening phrases of each antecedent are themselves clave-like, in that they contain the same kind of offsetting rhythms (i.e. groups of 3) that are present in clave patterns. These are answered by the extended version of these kinds of rhythms in the consequent of subsection 2b, at 0:49.

It is this kind of sophisticated rhythmic symmetry in the sentence structure of Parker’s music that is often overlooked when analyses of his spontaneous compositions are attempted, but many musicians of this period intuitively grasped it. The structure has an Able Was I Ere I Saw Elba form, where the figure at the beginning of these phrases is balanced by the same figure at the end. If you listen to this entire passage as rhythm only, disregarding the pitches, then I think it becomes easier to hear the rhythmic patterns I’m referring to. In an example of one variation of this particular symmetry, the second half of the 3rd chorus (2:01 to 2:08) contains virtually the same antecedent-consequent structure as was played at 0:42, with a response that is balanced in a different way, but that still uses the same clave-like pattern.

[2:01] of Ornithology

This approach to balancing rhythmic phrases and the resultant dynamic rhythmic symmetry, are reminiscent of the phrases that tap dancers and drummers use. These devices are constant occurrences in Parker’s music, as demonstrated in this song, and Navarro and Powell demonstrate much of the same tendencies. Of course, all of this is occurring so rapidly that there is no such analysis as I am giving here is involved on the part of the musicians. But I do think that these kinds of balances are involved in the feel of the music, and this is what contributes to the music’s effect. I believe that the initiated (the musicians who are near Parker’s musical level) are the first who are affected, then they transmit the information and influence the musicians just below their level, and so on. The collective impact of these concepts (albeit necessarily in diluted form) eventually gets communicated to the public’s ear.

The types of rhythms that Parker plays at 1:05 are similar to things that I’ve heard drummers from the African Diaspora execute. If you listen to it purely as rhythm, you can imagine a drummer playing exactly the same kind of phrase – in fact, Blakey does play parts of the phrase with Bird, and you can hear Bud stressing the same rhythmic weights, what I call pushing the beat. As with the woman’s exclamation at the beginning of his solo, I believe these lightning fast musical responses were as internalized in Bird’s playing as fans’ spontaneous responses at sporting events.

At the top of 3rd chorus (1:40), Bird executes one of those tricks that I think he learned from pianist Art Tatum, of turning the form around by starting it 2 beats early. This is not easy for a melodic player to do, as your spontaneous melody has to be strong enough that it suggests the displacement. You can even feel Bird stop to think about what he is about to do before he plays it.

Skipping ahead, after Fats tells his outstanding story and Bud Powell takes an absolutely killin’ solo, the two choruses of trading between Parker and Navarro are absolutely hair-raising.

6:09 has one of those crazy cartoon quotes followed by ridiculous cram. Two guitarist friends reminded me that this quote is from the song Jarabe Tapatío, known in English as the Mexican Hat Dance. The original form of the melody is:

Fats responds with a similarly shaped answer.

At the top of the second choruses of the horns trading (6:25), Bird plays this modulating tetrachord figure which he subtly changes to match the underlying structure of the song, played in his typically laid-back manner, and the groove is killin’:

![]()

The antecedent is structured as a Lydian tetrachord, in this case G A B C, with a Bb passing tone added:

![]()

However, the consequent contains a Dorian tetrachord, with a B passing tone added:

![]()

(Notice that the references to the terms Lydian and Dorian follow the Medieval terminology for these structures, which are based on the the top fourth of the Medieval Lydian and Dorian modes, referred to as ‘species of the fourth’ in Medieval times.)

Both forms of this tetrachord are plentiful in Bird’s spontaneous melodies and are among his favorite melodic structures. Even if you did not know the underlying harmonic structure of the song, you could discern the melodic structure by listening to how Bird emphasizes the second pitch from the top of the tetrachord, demonstrating which are the main tones and which are the passing tones. This again shows the importance of rhythm and stress in this music. Also in the consequent, Bird contracts the end of the phrase, again highlighting the structure of the tetrachord. Aurally this subtle change would probably be unnoticed by most listeners, which is the point, as in this case the consequent is really a subtle paraphrase of the antecedent. There is functional symmetry involved here, as technically the beginning of the two phrases contain the same pitches, but the B and Bb change function relative to the two tetrachords. In the first figure (1st measure), B natural is functionally part of the tetrachord and Bb is the passing tone, whereas in the second figure (middle of the 3rd measure) Bb is functionally part of the tetrachord and B natural is the passing tone.

At 6:41 Parker plays another strong clave-like figure, followed by a cram. Finally, I love the spontaneous harmonizing that Bird does on the out head, particularly the melodically symmetrical phase at 7:39, with the Db pickup to the next phrase (well, closer to D-flat than D-natural) being the symmetrical axis of the preceding 10 pitches:

![]()

These are just a few examples. There is so much going on in this song that I’ll just have to stop talking about it! The main point for me is how much we can learn from these very advanced techniques. So much more is going on than just swinging – however, Bird does that too.

6. TRACK: Mango Mangue

ARTIST: Charlie Parker

CD: The Charlie Parker Story

Musicians: Charlie Parker, alto saxophone with Machito And His Orchestra: Mario Bauzá, Frank “Paquito” Davilla, Bob Woodlen (trumpets); Gene Johnson, Fred Skerritt, alto saxophone; Jose Madera, tenor saxophone; Leslie Johnakins, baritone saxophone; Rene Hernandez, piano; Roberto Rodriguez, bass; Luis Miranda, conga; Jose Mangual, bongo; Ubaldo Nieto, timbales; Machito, voice, maracas.

Recorded: New York, December 20, 1948

The kinds of shifts in phrasing that we looked at in Perhaps are even more apparent in Mango Mangue, especially against the backdrop of the static harmonic material, a rarity in Parker’s musical repertoire – in fact, rare in the music of this time period. Parker was one of the few musicians of that era who could really wail over a vamp. Most of the cats back then did not know how to blow over one static harmonic palette, with the exception of blues-based improvisations, as their entire improvisation language was constructed around playing through an environment that involved moving chord changes. That was the difference between Parker and many of the people influenced by him. Bird was primarily a melodic player who played through keys. Most of the people influenced by him played through chord changes (this is Dizzy Gillespie’s way of characterizing what Bird did). Not that Bird had no knowledge of chord structure – it’s just that he had an intuitive gift for melody and melodic patterns that allowed him to adapt his language to a variety of music genres.

Again to quote Mingus (http://www.mingusmingusmingus.com/Mingus/what_is_a_jazz_composer.html):

“Bud and Bird to me should go down as composers, even though they worked within a structured context using other people’s compositions. For instance, they did things like ‘All The Things You Are’ and ‘What Is This Thing Called Love.’ Their solos are new classical compositions within the structured form they used…”

“For instance, Bird called me on the phone one day and said: ‘How does this sound?’ and he was playing ad-libbing to the Berceuse, or lullaby, section of Stravinsky’s ‘Firebird Suite!’ I imagine he had been doing it all through the record, but he just happened to call me at that time and that was the section he was playing his ad lib solo on, and it sounded beautiful. It gave me an idea about what is wrong with present-day symphonies: they don’t have anything going on that captures what the symphony is itself, after written.”

So Mingus considered Parker a composer, a spontaneous composer, and it is apparent from this quote that Bird had the ability to improvise on a variety of structures. We can only imagine what progress would have been made in the area of orchestra music had the great spontaneous composers been given access to the symphony orchestra with all of the colors it presents. However, Bird’s melodic structures on this recording of Mango Mangue are not really out of the ordinary – for him at least. It is because of the timing and rhythmic sophistication of Parker and the accompanying musicians that I picked this example.

At 0:46 the bongos execute a beautiful rhythmic voice leading passage (started by the congas), beginning with a setup on the third beat – and then, starting on the following third beat, playing 2 identical patterns that are each contained in 4-beat lengths – then again, starting on the following third beat, playing 2 identical patterns that are each contained in 3-beat lengths. This has the effect of shifting the start of the phrases from the third beat to the second beat, and leading to the first beat at the beginning of Bird’s solo. Again this is a demonstration of establishing a pattern, then altering it to rhythmically to voice-lead towards a specific target point in time, to either set up another event or to terminate a process.

The shifting diminished harmonies of the saxophones are beautiful, not often heard in American popular music at that time, and it is uncanny how Bird’s phrases fit perfectly melodically with the shifting textures from about 1:05 to 1:19 of the song. But what really turned me on to this song is the ‘call and response’ montuno section at 2:11 and how Bird’s spontaneous rhythms mesh perfectly with the Cuban players. Passages like this made me realize how often Parker’s playing contained clave-like rhythmic patterns, a clear example of African-retention. Even though the clave cannot be clearly heard, by listening to the cáscara pattern in the previously referenced section at 0:46 of the song you can orientate yourself to the clave (clave on top below):

Example at 0:46 of Mango Mangue, clave (top) and cáscara (bottom):

The phrase beginning at measure 9 in the example below (2:18 of the recording) and the phrase at measure 25 (2:32 of the recording) show how Parker’s stresses hookup with the clave and cáscara at key points in the phrasing of both.

Example at 2:11 of Mango Mangue

Based on this musical evidence, I believe that Parker played a larger role in integrating these two musical cultures than he is usually given credit for. Bird is usually given a minor mention when historians talk about the merging of African-American and Afro-Cuban music. However, Machito and Mario Bauzá paint a different picture. Machito has said that Parker was involved with his orchestra of Cuban musicians long before Norman Granz suggested making the recordings in 1948, and even before they met Parker, Machito and Mario Bauzá knew of Bird’s music, and Bird knew of their music. Machito declared with modesty, “Charlie Parker era un genio, yo no era nada comparado con él.” – “Charlie Parker was a genius, I was nothing compared to him.” (http://www.ryc.cult.cu/antesenpapeltextosleonardoacosta.htm). I also read where Bauzá remarked in an interview that Parker’s rhythmic improvisations fit naturally with the rhythms that the Cuban musicians were playing at that time, and that Bird was one of the only musicians from America whose rhythms fit well with theirs. By the way, in this performance Machito’s rhythm section is killin’!

7. TRACK: Groovin’ High

ARTIST: Charlie Parker

CD: Diz ‘n’ Bird at Carnegie Hall (Blue Note)

Musicians: Charlie Parker, alto saxophone; Dizzy Gillespie, trumpet; John Lewis, piano; Al McKibbon, bass; Joe Harris, drums

Recorded: New York, September 29, 1947

Parker was on fire during this concert, in top form. The rhythm section was not the greatest, but Bird was soaring. This is not the most creative of the Parker recordings I’ve heard (it’s certainly no slouch), but it is very refined playing on par with his famous strings version of Just Friends. From what I read, they brought Bird on stage for this quintet concert, which was sandwiched between two sets of Dizzy’s big band.

I dig this 1947 Carnegie Hall concert more than the May 15, 1953 Massey Hall concert in Toronto, where the musicians were distracted – they were running across the street between solos to check out the ongoing heavyweight championship fight in Chicago between Rocky Marciano and Jersey Joe Walcott (Marciano won by first round knockout)! Also, I always felt Mingus ruined the recording with the bass overdubs he did later – the bass is way too loud and playing on top of the beat.

Parker’s incredible time feel is on display from the moment he takes his break. He swings hard, even more evident here because during these four measures he is playing unaccompanied. The song begins in Eb major, but just before Bird’s solo the music modulates during an interlude to Db major, then, after a second interlude, back again to Eb major for Dizzy’s solo. Yard’s solo break contains a classic example of what I call cutting corners, where Bird takes this one path, then, beginning with his characteristic rhythmic vocal-like sigh just after the 8th beat of the break, moves briefly into a harmonic path in the area of Amin6, before falling back into the subdominant Gb major (of Db major). In this case the melody that he plays is more melodic voice leading than harmonic, as Bird’s melodic trajectory is aimed towards the high F and Ab, both pitches that have a dominant function from a melodic perspective in the key of Db major. So functionally this final phrase is a subdominant-to-dominant progression.

Parker’s solo break on Groovin’ High:

For the next three choruses, Parker gives a clinic on economy, telling his story with a compact approach, getting right to the point. His musical sentences are perfectly balanced without being predictable – he was a master of intuitive form. But what I want to discuss here is the loose precision that is demonstrated, a kind of playing that is extremely relaxed and variable and yet at the same time extremely detailed. This kind of laid-back, behind-the-beat, loose accuracy seems to have been the norm with players like Art Tatum, Don Byas, Bird and Bud Powell – in Chicago we used to call it the beginner-professional sound. The expression of rhythms and modes is so precise that repeated detailed listening is like reading an advanced music theory text, only a text that reveals more on each reading, and the words are in motion on top of it! In this sense it’s like the oral storytelling traditions, but here the information is encoded in musical symbolism. For this reason, I’ve always felt that this music really was telling stories, on many different levels.

8. TRACK: Confirmation

ARTIST: Charlie Parker

CD: Diz ‘n’ Bird at Carnegie Hall (Blue Note)

Musicians: Charlie Parker, alto saxophone; Dizzy Gillespie, trumpet; John Lewis, piano; Al McKibbon, bass; Joe Harris, drums

Recorded: New York, September 29, 1947

The melody itself is a theory lesson. So much subtle detail is involved that it is rarely played this way by modern musicians. Parker normally soloed first when he played with Dizzy – Birks said it was because when Parker played first, he (Diz) was inspired to play at his best. What’s extraordinary is not only Parker’s virtuosity, but the fluidity of his ideas and how they proceed from one to the next in such a conversational manner. Again Bird only takes three choruses, but he tells an epic story in this short period of time.

There is a lot of cramming in this spontaneous composition. Cramming is a term I first heard used by Dizzy in his autobiography To Be Or Not To Bop when he talked about Parker squeezing a longer rapid phrase into a smaller time space, a phrase that was not simply double time but some other unusual rhythmic relationship to the pulse. There is plenty of it in this version of Confirmation, and not all of it rapid. Bird had the ability to land on his feet like a cat after playing some of the most outrageous rhythmic phrases. But the key to what Yard was doing was his incredible time feel, so smooth that the phrases do not even feel odd in any way. In fact, most of the players who imitate his style have far less rhythmic variety in their playing. Obviously the impression that they get from Parker’s playing is that he is playing a steady stream of notes, all of the same rhythmic value. But nothing could be farther from the truth. Again, the conversational aspect of Yard’s playing is always on display, the way he is always in dialog with himself, even when there is not much in the way of dialog coming from his accompanists (as is the case in this recording).

My analysis here comes mostly from a rhetorical and affections perspective which deals with the poetics of the music. This perspective is the one most stressed in the African-American community.

Parker opens with a very strong melodic statement. I love the way Bird plays in sentences that straddle the square (every 2 or 4 beats) progression of the harmony. Bird’s statements flow right through several tonal changes, his sentences mutating and reflecting the changing tonalities as they move, while still being very strong melodies, perfectly balanced. His statements make perfect intuitive melodic sense to the uninitiated listener while simultaneously providing worlds of sophisticated information for experienced musicians. The exclamation starting at the second measure of the second eight is incredibly vocal and moves into a blues-tinged statement. This second eight section ends with a very strong melodic sentence at 1:09 that terminates with a dominant-subdominant-tonic melodic progression, instead of the normal dominant-tonic motion. Parker normally has strong ending statements just before the bridges, but these terminating statements traverse an incredible variety of harmonic paths.

The feeling of the bridge is like when another person interjects with a different subject, or adds another part to the story. Of course this is what occurs harmonically as well, but I am referring here only to the character of Parker’s melodic statements – it’s almost as if another person is talking at this point. These statements then get resolved going into the last eight of this first chorus, as if returning to the original speaker. This first chorus concludes with a very strong closing melodic statement that sums up the previous statements, which may be the quote to some standard that I don’t know. I’ve always heard this last phrase at 1:32 as saying, “Well…, but it’s always gonna be like that.”

The beginning of the second chorus responds with “but you know we’ve gotta keep on goin’,” which is my personal interpretation of this response to the end of the first chorus. This second chorus is by far the most involved and complex part of this story, and this middle chorus feels like the meat of the story. I noticed that the most complex passages come in the second eight and the bridge of this second chorus – these sections are symmetrically right in the middle of this entire spontaneous composition! Now, either Bird planned it this way or he has a hell of an intuition in terms of form – or both. There are several advanced rhythmic devices, double-timing, rhymes (the phrase at 1:38 rhymes with the phrase at 1:41), and backpedaling – phrasing from the offbeats (1:46). The double-timing phrases that begin inside the fourth measure of the second eight (1:52) still contains all the rhythmic complexity and clave-like phrasing that Parker is known for – however, the accuracy of these lightning fast statements is absolutely frightening! This hyper phrase ends in a question, both harmonically (in the form of a secondary dominant) and melodically (the rise of the melody at this point). It’s answered moments later with a bluesy statement, a rising subdominant – descending whole-tone dominant phrase.

Second Chorus – second 8 of Confirmation

These complex double-time statements continue in the bridge and represent the height of the story. The opening melody of the bridge moves through several unusual tonal areas which I hear as:

– / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / /

| Cmin | Dbmin6 F7 | Bbmaj Ebmaj Bbmaj | Bbmaj |

This Cmin to Dbmin6 to F7 progression was something that Parker played often, but it’s one of those esoteric dominant progressions which never caught on among the majority of musicians who were influenced by Bird. It really says something about the level of Yard’s intuition that he could arrive at such a progression seemingly by feeling and ear alone, although I am by no means certain that this was the approach he used.

Second Chorus Bridge of Confirmation: